One of the best parts of being a documentary filmmaker is that everyday work can take you on incredible trips and connect you with inspiring people around the globe. Recently, one of our field producers, Mark Jackson, embarked on one such trip from his home in Cape Town, South Africa, to Bangalore, India. His goal was to create a short film to provide a taste of the Science for Monks program, which our friends at the Sager Family Traveling Foundation & Roadshow sponsor. Here are some of his recollections of the experience.

I like to think that I learn from each person I meet while producing a short film, but working with the Tibetan monks in India stands out as a particularly special job.The focal point of the Science for Monks program is the Dalai Lama Institute for Science, which is located about 100 kilometers outside Bangalore. It wasn’t easy to get there. I had a middle-of-the-night layover in Dubai, and my taxi ride from Bangalore proper out to the center was far from tranquil. In the old city, the streets were packed with people and cows and bikes and rickshaws and everything from 1950s taxis to the very latest high-tech, top-of-the-range cars and buses, all going in different directions.

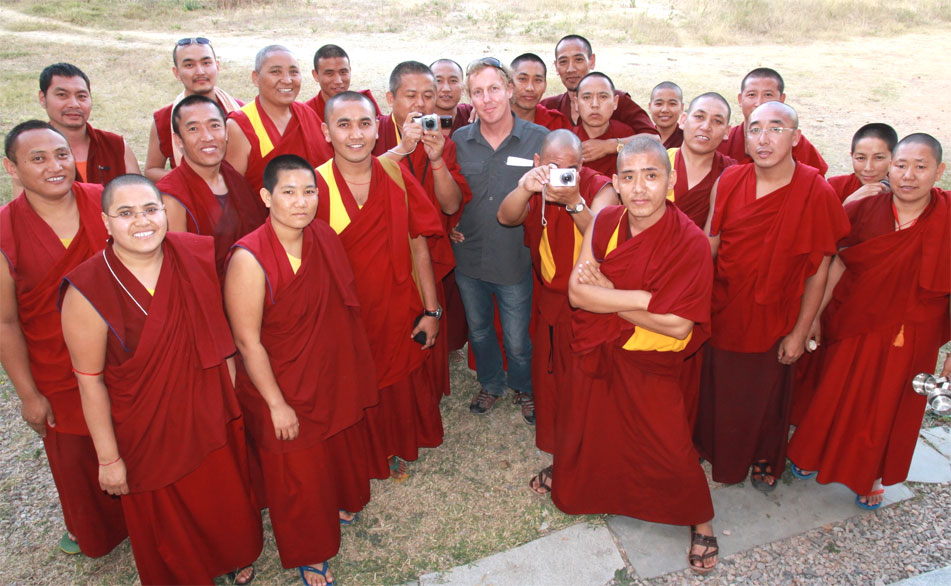

By the time I arrived at the institute, I was expecting a stunning monastery set against a mountainous backdrop. What I found was a half-finished collection of buildings on the side of the road. No paint on the walls. No tile on the floor. In places, exposed rebar jutted from the cinderblock. My apartment was located just down the hill from the teaching academy and was spartan to say the least, with a cot in the corner, a few curtains on the wall, and a window overlooking a yard where people were burning grass. Suffice it to say, I wasn’t sure exactly what I had gotten myself into.Then I met the monks. They were an amazing group of people, about thirty or so in number ranging in age though mostly in their twenties and thirties. I was immediately welcomed over lunch with doughballs, fried bean curry, fried cabbage, and lentil soup—a meal they prepared themselves and eat most every day. They laughed a lot and played jokes on each other. In some ways they were surprisingly modern. I was amazed to see most of them pull out cell phones, and more than a few, it turned out, had iPads. One of the western scientists told me that he was flabbergasted when he first arrived to learn that most of the monks had Facebook profiles and engaged in social media on a regular basis.I started filming the monks that afternoon. My goal for the film was twofold. The first was to offer a taste of how the development of science learning in monasteries can help Tibetan Buddhism stay with the times and expand its influence. The Science for Monks program started in 2001 in response to the Dalai Lama’s request to introduce science education to the monastic curriculum. Since that time, Science for Monks has brought Western scientists to India to implement workshops designed to share salient concepts of Western science with Tibetan monastics in exile. The Sager Family Foundation is a critical partner for the program. The foundation works with the Library of Tibetan Works & Archivesto attend an upcoming Science for Monks exhibit in San Francisco. to grow and sustain the Library’s historic undertaking. The second purpose of my film was to inspire potential donors and partners to support the program and to attend an upcoming Science for Monks exhibit in San Francisco.

Filming was in some ways a challenging experience; it was hot out (about 95 degrees Fahrenheit) and given my schedule we didn’t have much time to work with. The center had some electricity, but there were few lights on after nightfall, which made filming after sundown or before sunrise impossible. But these are also the joys of being a documentary filmmaker, making it work no matter the setting or the obstacles. And it’s a big appeal of working on a micro-documentary project: you get the freedom to be a real filmmaker, not just a technician in a cookie-cutter setting.

As it turned out, the monks were incredibly comfortable on camera, making it easy to capture them at work, where their studious calm and compassion were contagious. Through the process of filming over a three-day period, I came to better understand what monks do and how they operate. Simply put, monks focus on peace and humanity. They spend all day discussing how to rid your heart of anger, hate, and all the troubles that we carry. I watched as they compiled an astounding list of questions for western scientists. Questions like: “You don’t work with religious leaders, yet you work with politicians. Why?” or “Why make weapons that kill?” and “What is science really doing for the majority of people in the world, who are poor?”

In an interview on the second day I asked a monk, “What is it about Buddhism that Westerners get wrong?” His reply: “Westerners think Buddhism is magic. We have some rituals, but it’s not much magic.” Over lunch he explained a bit more, something to the effect that perhaps Westerners have forgotten that all life is magic. I got to feel a bit of that magic the day I left, when I awoke at sunrise to film a 15-minute prayer meditation, the scene that starts the microdoc. I left those monks with my heart full and promising myself to come back and spend more time with them … one day soon.